In 1854, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois proposed a bill to organize the Territory of Nebraska, a vast area of land that would become Kansas, Nebraska, Montana and the Dakotas. Known as the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the controversial bill raised the possibility that slavery could be extended into territories where it had once been banned. Its passage intensified the bitter debate over slavery in the United States, which would later explode into the Civil War.

The discovery of gold in California in 1849, and California’s subsequent request to become a state, sparked a fierce battle in Congress. As California had banned slavery, its admission to the Union would upset the fragile balance between slave and free states. By the end of 1850, Senator Henry Clay (with Douglas’ help) had persuaded Congress to accept the Compromise of 1850. By its terms, California entered the Union as a free state, while the territories of Utah, New Mexico, Nevada and Arizona (all acquired in the Mexican-American War) were left to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery within their borders.

Did you know? Kansas was admitted as a free state in January 1861 only weeks after eight Southern states seceded from the union.

Douglas hoped this idea of “popular sovereignty” would resolve the mounting debate over the future of slavery in the United States and enable the country to expand westward with few obstacles. But the Compromise of 1850 (especially the strict new Fugitive Slave Act it contained) galvanized the abolitionist movement and fueled mounting debate over whether the institution of slavery should be allowed to expand along with the nation.

Fugitive Slave ActsKnown as the “Little Giant,” Douglas was one of the country’s most prominent politicians by 1854, and was seen as a likely future president. He was also a big booster of the planned transcontinental railroad, which would provide faster, more reliable transportation across the country. Douglas wanted the railroad to be built along a northern route that would go through Chicago as well as a vast area of land known as the Nebraska Territory, which had been included in the Louisiana Purchase.

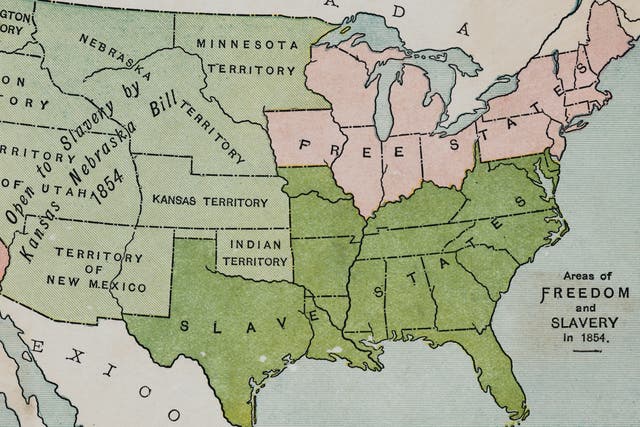

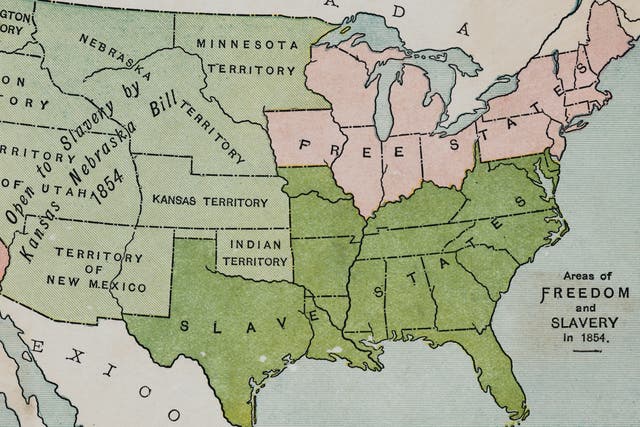

Southern slaveholders and their allies in Congress opposed Douglas’ initial bill to organize the Nebraska Territory. In 1821, the Missouri Compromise had outlawed slavery everywhere in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36º 30’ parallel, and the two proposed territories lay north of this line.

Douglas needed proslavery votes to pass his “Nebraska Bill,” as it was known at the time. To get them, he added an amendment that repealed the Missouri Compromise and created two new territories, Kansas and Nebraska. Settlers in each territory would vote on the issue of whether to permit slavery or not, according to the principle of popular sovereignty.

Kansas-Nebraska ActDespite fierce opposition from abolitionists and Free Soilers, as those who opposed extending slavery into new territories were known, the Senate passed the Nebraska bill. President Franklin Pierce signed it into law on May 30, 1854.

In the months before the bill’s passage, most of the Native American groups living on the land in question signed treaties ceding their land to the U.S. government, and all were eventually forced to move south to reservations in what is now Oklahoma.

In the North, where abolitionist feeling was growing, many condemned Douglas for striking down the Missouri Compromise and paving the way for slavery’s extension into the territories, rather than its ultimate extinction.

There was no question that Nebraska would be a free state, but the fate of its southern neighbor, Kansas, became a matter of fierce debate. Pro- and antislavery activists flooded into the new Kansas territory, each side seeking to turn popular sovereignty to their own advantage. As the two sides traded outbursts of violence and intimidation, “Bleeding Kansas” would generate national headlines, further inflaming sectional tensions over slavery’s future.

Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act also had a profound political impact. Debate over the bill split the Whig Party, which ultimately dissolved, and split Douglas’ Democratic Party along sectional lines. In one of the most heated moments in the debate, proslavery Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina, resorted to beating antislavery Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with his cane on the Senate floor in 1856.

Opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act inspired the formation of the Republican Party, which became the nation’s leading antislavery political party. It also drew Abraham Lincoln, a former one-term congressman from Illinois, back into the political arena. By 1858, Lincoln’s eloquent argument against slavery’s extension would go on display in a now-famous series of debates with Douglas, as Lincoln unsuccessfully challenged the “Little Giant” for his Senate seat.

Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 presidential election marked a decisive defeat not just for Douglas—who ran as the northern representative of the divided Democrats—but for his belief that popular sovereignty could prevent national politics from dissolving into a regional conflict over slavery. In fact, the Kansas-Nebraska Act served to further divide the nation, and served as a crucial step along the path to the Civil War.

A definitive biography of the 16th U.S. president, the man who led the country during its bloodiest war and greatest crisis.

Ross Drake, “The Law That Ripped America in Two.” Smithsonian, May 2004.

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (W.W. Norton, 2010)

Kansas-Nebraska Act - May 30, 1854. U.S. Senate.

Zach Garrison, Kansas-Nebraska Act. Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. Kansas City Public Library.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen and Christian Zapata.